Biography

Giuseppe Dessì was born in Cagliari on 7 August 1909 to Francesco Dessì Fulgheri and Maria Cristina Pinna.

A good part of his childhood and adolescence was lived in Villacidro where he stayed with his mother in the home of his maternal grandfather, due to his father’s continual transfers as a non-commissioned officer in the Italian Army. Upon his father’s return after the war – as General Dessì – the family transferred to the home that is now used as the Foundation’s headquarters.

He was a restless and “undisciplined boy” but he was also an avid and insatiable reader, as he liked to define himself. Dessì was not able to complete his regular studies and studied with many tutors, among whom the priest Don Luigi Frau.

"Pessimo scolaro, riottoso e disordinato, fuggito dal collegio, fui fin dall’infanzia un lettore avido e insaziabile. Quasi completamente abbandonato a me stesso, leggevo tutto ciò che un ragazzo della mia età non avrebbe dovuto leggere. Delle mie letture nessuno si curava né per consigliarmele né per proibirmele. Continuai a leggere tutto ciò che mi capitava tra le mani, indiscriminatamente".

(A terrible student, riotous and disorderly, I ran away from school. But even as a small child I was an avid and insatiable reader. I was almost completely abandoned unto myself, I read everything that a boy of my age should have read. No one paid any attention to what I read, no one offered any advice and no one forbade me to read anything. I kept on reading everything I came across, indiscriminately)

It is during this period that he gained access to a library kept in a fitted cupboard that had belonged to his grandfather. The books he read were mostly philosophical in theme , (Leibniz, Spinosa, Cartesio, Voltaire, Diderot, Comte, Darwin e Spencer) and were very upsetting to him as he describes:

"Senza che nessuno se ne accorgesse o potesse nemmeno lontanamente sospettarlo mi eri andato facendo del mondo un’idea deterministica estremamente rigorosa. Consideravo ogni mia azione, anche il minimo gesto, come l’anello di una catena di cause ed effetti che aveva inizio con la creazione del mondo e dalla quale non avrei mai potuto liberarmi, anzi arrivai a pensare che il solo atto di libertà possibile fosse il suicidio.”

(Without anyone noticing or even suspecting in the least, I was developing an extremely strict deterministic idea of the world. I thought that my every action, even the tiniest gesture, was like a link in a chain of causes and effects that originated with the creation of the world from which it would be impossible for me to break free, to the contrary, I came to the point of believing that the sole possible act of freedom was suicide)

His father came to his aid: he casually examined the material his son was reading and considered these books inappropriate to a sixteen year old boy. He gave him a copy of “Orlando Furioso” as a gift in an edition that had neither notes nor preface”. Reading Orlando for Dessì was like discovering poetry and recovering that balance which he had lost.

"E sono felice di dovere, anche questo, a mio padre. Fu come se mi avesse dato la vita una seconda volta. L’incontro con la poesia nel modo più felice e perfetto".

(I'm happy to owe this (as well) to my father. It was as if he had given me life for the second time. The encounter with poetry on the happiest, most perfect way)

The partial balance he found enabled the young boy to begin his upper school studies, albeit with a delay, in Cagliari where he began to attend the Dettori in 1929. It was here that he met people who would be essential to his development as a man, intellectual and as a writer. He met Delio Cantimori, his philosophy and history teacher. Cantimori also introduced him to Claudio Varese. This philosophy teacher helped Dessì to overcome his deep existential struggle due to his former readings and suggested new directions for his intellectual development: Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Rilke, Mann, Hesse and Proust, authors with whom the young man fell deeply in love. An intense relationship based upon respect and trust was established between the student and his teacher and Cantimori was the one who suggested Dessì study at the Normale in Pisa. The young Dessì admired the order and clarity of his teacher, who was practically his contemporary. This sense of calm would become an essential tool for him to come face to face with and control everything that could have represented poverty and disorder in his native Sardinia.

Dessì was rejected at his admission exam, but he always stated that he had attended this Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa in the sense that he was so close to that environment that he made friends with many young people who attended the institute, friendships that would last a lifetime. During those years in Pisa he made some essential acquaintances, many of whom were in Cantimori’s circle: Aldo Capitini, Claudio Baglietto and Carlo Ludovico Raggianti, besides Claudio Varese, Cordié, Russo and Momigliano. Dessì earned his university degree in Liberal Arts in 1936 in this climate of intellectual fervour and exchange.

The Tuscan experience was an essential moment in his intellectual and human development as well as his political-social awareness in a complete way. Dessì belonged to an association of young intellectuals in which the political-cultural debate of those years was fervently alive. The concept of culture as a vital ethical-political substance was in clear contrast with the prevailing Fascism that denied the cultural credo they had embraced. A fundamental figure in this period was Claudio Baglietto who, in the name of his anti-Fascist ideology, chose exile; Dessì was inspired by him to create one of his most important characters that would make his return in various works, a sort of alter ego of the writer himself: Giacomo Scarbo.

His career as teacher in middle- upper schools began during the following years, first in Bassano del Grappa and then in Ferrara, where he met with his friends Varese, Franco Fulgheri, Bassani and others. In 1939, he was appointed chief of the Education Department in Sassari and then Inspector at the Ministry of Public Education. This career forced him to change residences often: Sassari, Ravenna and Rome, where he lived a great deal of his life, until his death in 1977. He was the “Continental” Sardinian who always carried his deep sense of belonging to Sardinia with him, particularly his relationship with Villacidro.

Nostalgia for the island and his love of the places in which he grew up are a constant element and the Island, with its nuances, history, sense of time, its language, silences, colours and fragrances forcefully emerge from the protagonists of his literary works. His literary activity began in 1937 with the publication of articles for Torino’s La Stampa newspaper as well as in “La Nuova Antologia”, “Primato”, "Porta-Nova”, “L’Orto”. The following year, in 1938, his collection of short stories "La sposa in città": (The Bride in the Town) consecrated him as an author:

Non senza fatica stesi la semplice storia dell’uomo di San Silvano dai capelli brizzolati. Lo feci tornare a San Silvano dopo lunga assenza, perché potesse sentire come cosa nuova tutto ciò che invece aveva conosciuto fin dall’infanzia; e lo feci elettricista perché potesse portare a San Silvano un elemento nuovo: quelle lampade che si accendevano tutte d’un colpo, la sera, sul paese già buio.

(It was an effort to write the tale of the grey-haired man from San Silvano. I made him return to San Silvano after a long absence so he could feel everything he had been familiar with since his childhood as something completely new; and I made him an electrician so he could bring a new element to San Silvano: those streetlamps that lit up all at once in the town that had already gone dark in the evenings).

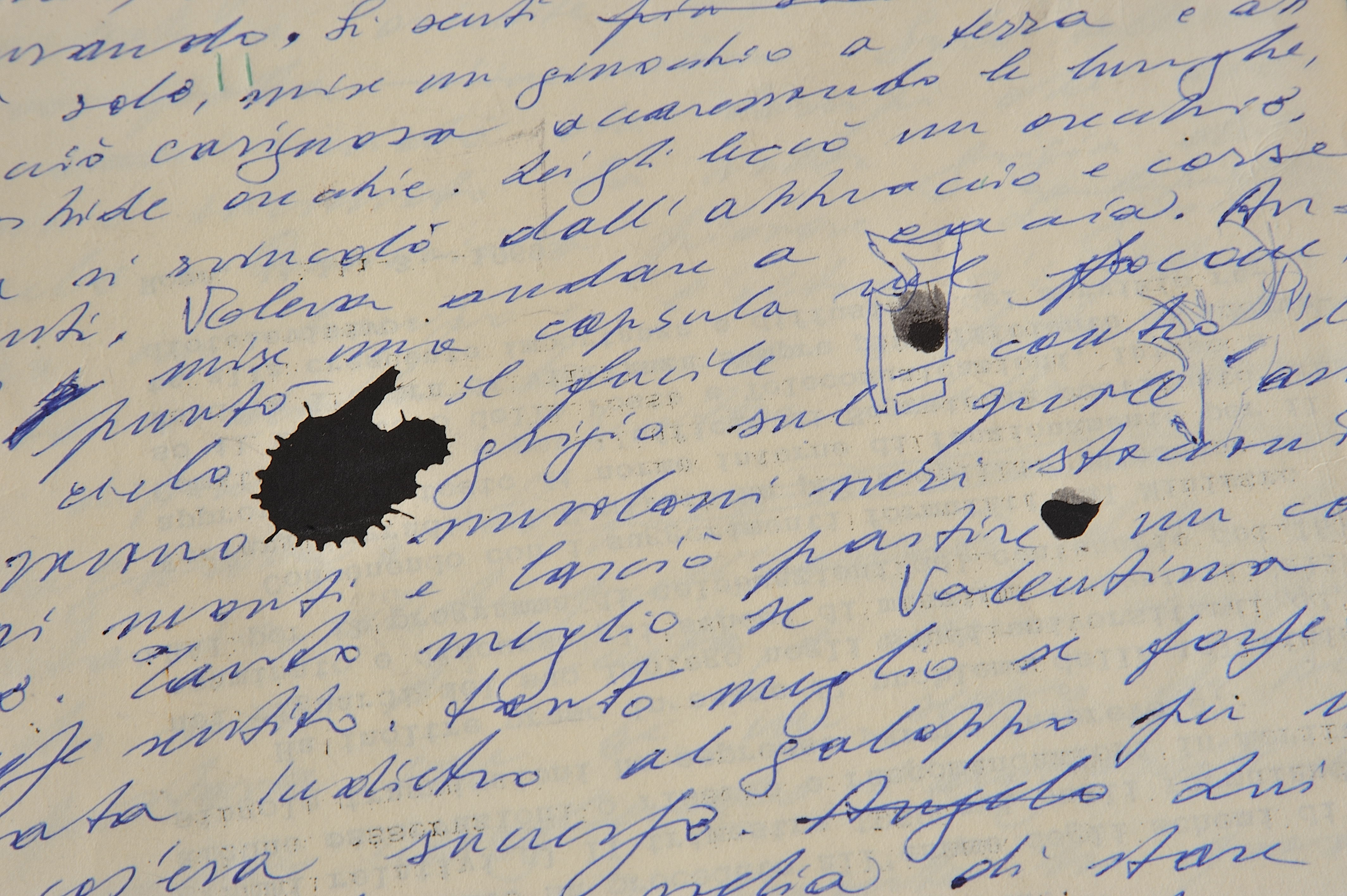

The pages in his diaries left traces of the intense activity that came before and accompanied his writing:

i pensieri, le riflessioni sui luoghi e i personaggi: Per questo ritrovo dentro di me il piacere della parola scritta. Essa è pura, ma non isolata: è un frutto ma non staccato dal ramo, un frutto che deve conservare la qualità della terra in cui le radici si nutrono. Vale la pena di scrivere solo per raccontare fatti che non sono accaduti, o per “travisare”, trasformare, rivivere con la fantasia fuori del tempo reale, nel tempo della memoria, i fatti accaduti. Vale la pena di parlare di Elisa, che non è mai esistita, e di Boschino, che continua, completa, interpreta, spiega …E’ per questo Villacidro, con tutto il carico di dolor e di disgusto che si porta con sé, che chiude in sé, mi da un fervore unico di ricordi. Quando tu te la pigli con Villacidro tocchi qualche cosa di troppo vivo, troppo nudo e delicato. (…) Per questo tu non devi prendere un tovagliolo di lino tessuto in casa mia un secolo fa e sbatterlo in fondo al baule. Mi fa male.

(...the thoughts, considerations of the places and characters: this is why I rediscover the pleasure of the written word within my life. It is pure, but never isolated: it is a fruit that is not cut from the branch, a fruit that must preserve the quality of the soil in which the roots feed. It is well worth the effort to write exclusively to tell of events that never took place, or to “twist”, transform or relive those which actually happened with your imagination, out of real time, in the realm of memory. It is worth writing about Elisa, who never really existed, or of Boschino who continues, completes, interprets and explains…It is for this reason that Villacidro, with its load of pain and disgust which it carries and holds closed inside, gives me a unique fervour of memories. When you take offence of Villacidro you touch something that is still too alive, too exposed and delicate. (…) This is why you cannot take a linen napkin that was woven in my home a century ago and toss it at the bottom of a chest. It hurts me)

In 1939, Dessì published his first novel San Silvano, “the tale with and for memory”, with a narrative style that earned him the definition of “Sardinian Proust” from Contini. The lyric-memorial tone and flavour in this work are revealed in the large number of poetic vibrations and recollections..

The necessity to search for and analyse reality, giving space to the imagination without yielding completely to it is the foundation of the poetry of this writer. It is from this dialectic style that all of his other writings will come into being. In 1941, Dessì was living in Sassari as chief of the Education Department and brought the profound sense of his “continental” experience in its entirety to the group; it was here that Dessì and Borio founded the first local chapter of the reconstructed Italian Socialist Party. While living in Sassari he also collaborated with the weekly magazine “La Riscossa”. He inaugurated the first issue:

Sarà compito di questo nostro foglio settimanale discutere ora apertamente le idee che maturarono in noi negli anni di attesa, farle vivere di vita più larga ed arricchirle. E combattere, alla luce di quelle idee, la nostra battaglia, piccola o grande che sia, per quel dovere morale di partecipare alla vita politica che ci mosse dapprima e che tuttora ci anima.

(The duty of this weekly paper of ours is to openly discuss the ideas that have ripened within us during the years of anticipation, to allow them to live a more expansive existence and to enrich them. And to fight our battles – small or large as they may be – in light of these ideas for that moral duty of participating in the political life that initially set us into action and that animates us to this day.)

In 1942, the novel Michele Boschino proposes two different models: the first part is an objective quest conducted in the third person while the second part is written in first person with a clear cut and offers a subjective and introspective writing style; the interconnection of the two parts: the intellectual, European writer who observes the archaic, peasant world of the island and the characters from popular Sardinian life. Boschino is a fundamental passage in the writer’s literary and artistic career and the quest for balance and harmony between the two poetics are an integral part of all of his writings up to his masterpiece Paese d’Ombre (Town of Shadows).

Years of intense literary activity followed: the collection of stories Racconti vecchi e nuovi (Old and New Tales) was published in 1945 and La storia del Principe Lui (The story of Prince Him) was published in 1949. He then moved to Rome and published I passeri (The Sparrows) in 1955 and then two collections of short stories were published in 1957: L’isola dell’Angelo (Angel Island) and La ballerina di carta (Paper Dancer). Introduzione alla vita di Giacomo Scarbo (Introduction to the life of Giacomo Scarbo) was published in 1959 and in 1961 his Il Disertore (The Deserter) won the Premio Bagutta award, winning full consent of literary critics. Varese commented:

… i fatti sono penetrati e chiariti da altri fatti e la realtà disumana della guerra, il culto falsificante e totalitario dei caduti come eroi acquistano e trovano negli spostamenti interni e segreti della vicenda una simbolica interpretazione e una condanna.

(the facts are piercing and clarified by other facts and the inhumane reality of war, the falsifying and totalitarian cult of the fallen as heroes acquires and finds a symbolic interpretation and condemnation in the inner and secret movements of the events) (Varese)

Aside from being an author, Dessì was also a skilled playwright: he published the dramatic short story La giustizia (Justice) in 1958; Eleonora d’Arborea in 1964 and La Trincea (The Trench) was featured in the Drammi e Commedie dell’ERI in 1965. He also penned essays: Dessì wrote a collection of some of the most significant pages ever written about the island by famous authors in 1965, gathered in the elegant volume Scoperta della Sardegna (Discovering Sardinia). His participation in television and cinema must not be neglected. Dessì works on various documentaries and television programmes (most of which were dedicated to Sardinia) from 1942-1967. Cinema was a new and different way for him to tell of himself, Sardinians and of Sardinia:

Soltanto la possibilità di impiegare a mio modo i mezzi cinematografici, i darebbe la possibilità di esprimere ciò che sento cinematograficamente della Sardegna. Soltanto in un secondo tempo penserei al racconto. (…) Io potrei suggerire una quantità di temi per documentari; ma lo farei solo ad un patto: dirigerli io stesso. Perché sarebbe difficile trasmettere ad altri l’esaltazione che mi da, per esempio, un qualunque pezzo di terra sarda, dove io sento e posso individuare la contemporanea presenza della preistoria e della storia.

(The possibility of using cinematic means in my own way would give me the possibility of expressing what I feel cinematically about Sardinia. I would only give any thought to a story later on. (…) I could suggest a quantity of themes for documentaries; but I would only do so on one condition: I would have to be the one doing the directing. Otherwise, it would be difficult for me – as an example - to convey to others the exaltation that any piece of Sardinian land gives me where I sense and can detect the presence of both pre-history and history)

In 1966, the volume of short stories Lei era l’acqua (She was water) was released and in 1972 he published the novel Paese d’Ombre (Town of Shadows), winner of that year’s Premio Strega award with extraordinary consent. This is the work of a lifetime of which the writer had been thinking about since the days of San Silvano; pages in which his dual quest, the integral part of the poetics of this author, is put into concrete form in perfect fusion. Marco Virdis commented:

In Paese d’ombre la storia si impone rompendo ogni realtà fantastica come alternativa alla realtà, i grandi fatti storici dissolvono la cappa di immobilità preistorica e lo scrittore sente la necessità, forse il dovere, anche in un’altra prospettiva nel tentativo di cogliere nelle vicende dei personaggi la riflessa condizione di un popolo afflitto dai suoi mali endemici e travagliato dagli sconvolgimenti sociali.

(The story of Paese d’Ombre makes itself heard by smashing every fantastic reality as an alternative to reality itself, great historical facts dissolve the cloak of pre-historic immobility and the writer – in his attempt to convey from a new perspective - feels the necessity, perhaps even the duty, to gather the reflected condition of a people that is afflicted by its own native ailments and tormented by social upset) (Marco Virdis)

An unfinished novel called La scelta (The choice) was published posthumously in 1978. A collection was published in 1988: Un pezzo di luna (A Slice of the Moon) and Come un tiepido vento (Like a warm wind) and the publication of Diari (his diaries) in three volumes edited by Franca Linari and le Poesie (poems) edited by Neria de Giovanni. Villacidro has always been a privileged observation point in the literary world of Giuseppe Dessì, since his very first novel, San Silvano. His foundation of knowledge departs from San Silvano/Villacidro and inevitably returns to Norbio/Villacidro.

In 1964, Dessì became ill. He was bedridden, but this did not hinder him from his writing and it was during these years that Paese d’Ombre (Town of Shadows) and La scelta (The choice) were written. In 1965, he wrote to his lifelong friend, Claudio Varese:

Spero di meritare la vostra fiducia, di continuare a meritarla perché essere scrittori vuol dire essere scrittori a dispetto di tutto e fino all’ultimo.

(I hope to be deserving of your trust and that I can continue to do so because being a writer means being a writer in spite of everything and until the dying day)

Giuseppe Dessì died in Rome after a long illness on 6 July 1977. His remains are now in the cemetery at Villacidro, the centre of his world as man and writer, a place that had magnetically attracted him throughout his lifetime.